We were in Japan just a few months when my eldest daughter, Nanao, became functional in Japanese.

My husband Billy and I would come to rely on her to read notes from her teachers, as well as the kairanban—the circulating neighborhood bulletin that informs you about things like garbage disposal rules, local recitals, where to evacuate in the event of an earthquake.

Our other children, Mie, Mario, and Lila, born here, speak Japanese as their first language. They were all always the only foreign children in their schools and our community.

Socialized as Japanese, they didn’t see themselves as different, in any significant way, to their friends and classmates. Still, it couldn’t have been easy being the “only” anything, and surely there were challenges. One challenge Mie faced in elementary school was the time she came home and told me a kid “called me American!”

I had to inform her that she was indeed American, and that, in any case, it was not an insult.

The Americans

That the laws of nationality are universally arbitrary is highlighted by the fact that if a Japanese couple had children born in the United States, those children would have American citizenship. Mie, Mario, and Lila do not have Japanese citizenship. Nanao, born in Denmark, is not recognized as a Danish citizen.

Nationality is something named on your passport. It’s clear to me that no one is going to know much about me, my husband, or our four children by our being labeled ‘American’. And surely not by the various colors of our skin.

Billy and I — a gainfully employed, tax-paying, law-abiding couple — were in Japan fifteen years before we were granted a visa giving us permanent resident status.

And it’s a fact that we never said: “Let’s live in Japan.” We just let it unfold.

We have no regrets. We consider ourselves fortunate to have settled and raised our children in this country, culture, and society.

Classic childhoods

Living in Japan, our children had childhoods parents in some other countries might wish their kids could experience.

Our kids were free to roam. They’ve camped outside overnight with friends, and no adults. While still in elementary school, they rode the super-express train alone to distant cities. I never had an anxious stress-filled moment wondering if they were OK.

Now, my elementary school-age grandchildren who live in Tokyo, run around the neighborhood freely, play in the park until dark, and ride public transportation on their own.

Adjusting, adapting, accepting

When we first came to Japan, I wasn’t impressed that this society was described as ‘conformist’, ‘group-oriented’— in which people’s behavior is always concerned with its effect on the group.

But I came to see how this encourages people to be considerate, and that it contributes to maintaining stable and safe communities.

In this densely populated, openly interdependent society, this is considered common sense. From the Japanese perspective, excessive focus on individualism can be self-centered, leading to irresponsibility, and chaos.

Japanese society could not function as well as it does if each person made up the rules for themselves. Everyone following the rule it’s wrong to keep something that does not belong to you is why I could expect the wallet I left on the express train with ¥80,000/$800 in cash and no identification would be returned. Many foreigners living in Japan have a story like that to tell.

Settling down, settling in

We’ve now built our house in a jūtakudanchi (residential subdivision of single-family homes). A half-hour drive from the farmhouse at Futokoro Yama, this is not a cosmopolitan place. My neighbors speak Japanese exclusively. I can say, without exaggeration, my husband is the only person I speak English with on a regular basis.

That I didn’t have the opportunity to study Japanese formally is evident in the mistakes I continually make. Fortunately for me, the people I regularly interact with are forgiving. Like Sawaguchi-san, the farmer who gives me his homemade umeboshi, salted pickled plums, the staple condiment eaten with rice.

The other day when I saw him at the local pool where we swim daily, he told me he’d been absent because he’d broken his ankle. Sympathetically, I said it was too bad his ankle had wareta. He replied, politely ignoring my incorrect use of the verb to break (used for breaking, for example, a dish) that his ankle had “kossetsu shita” — fractured. I only have 5000 other examples like this.

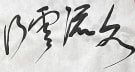

As Japanese is three quite discrete skills — speaking, reading, writing — I am happy I can say I can write it, with a brush. I’ve studied and practiced Japanese calligraphy, Shodō 書道 for forty years, attaining ni-dan, second-degree mastery.

Fifty years and counting

Unsurprisingly, it’s not that the question “What am I doing in Japan?” has never crossed my mind . It’s just that it doesn’t anymore.

I can’t say that I grew up here — but this is the country where I’ve matured.

Japan has changed me, and although I would not call it a metamorphosis, I know I am not the same person who came here all those many years ago.

Fifty years ago, I would not have guessed that in this ancient country, with all its old customs and formalities and daily obligations, its many written and unwritten rules, that I’d find so much that reflects my innermost sensibilities, and that I’d develop feelings of such deep attachment.

Quite frankly, I’m surprised that I didn’t leave, fifty years ago, when I found out the Japanese don’t dance at parties.

There was a lot I didn’t understand about Japan and its culture. It is now sometimes disconcerting to think of the many times I must have crossed the invisible lines of decorum and behavior that rule Japanese society, and that are practiced on a daily basis like a reflex.

However, early on I did see that there were cues, verbal and non-verbal, and that I could learn by showing a measure of humility and paying attention, and that I’d benefit by becoming a self-reflective and careful observer.

And in the process of embracing a culture so different from my own, and opening myself to new experiences, I discovered myself.

On my 20th birthday, I crossed the border from Spain into France. My 30th birthday went unnoticed until I saw the date on the stamp in my passport at the border crossing from Iran into Afghanistan.

While my travels are not over, when I turned eighty this year, I was at home, in Japan.

This is the final part of a 3-part essay.

I invite you to also read my memoir The View from Breast Pocket Mountain Grand Prize Winner of the 2022 Memoir Prize for Books.

Wow! They're all grown up, with big grands! How did they grow so old when we're the same??

Nationality is a legal term stated in your passport. If you were born in Japan and imigrated to the U.S. you are an American. But are you comfortable saying MAGA?